Engrosser’s Script: Understanding This Classic Calligraphy Style

What is Engrosser’s Script?

My IAMPETH Certificate of Proficiency In Engrosser's Script Application - 2022

I share my personal experience applying for the Certificate of Proficiency in Engrosser's Script under the IAMPETH Certificate Program in 2022.

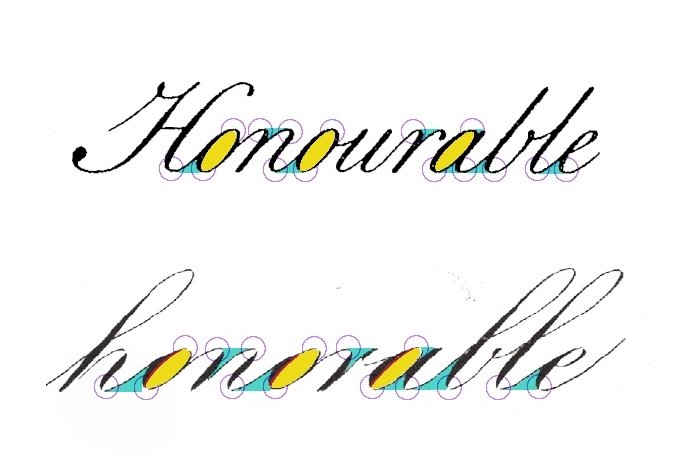

3 General Attributes - Script Analysis

I list out the top three overarching qualities that a script generally follows. They are, in my opinion, contrast, harmony and symmetry. I propose that these are the top three key observable features that make one’s script beautiful and visually balanced, no matter which style of script you’re studying.

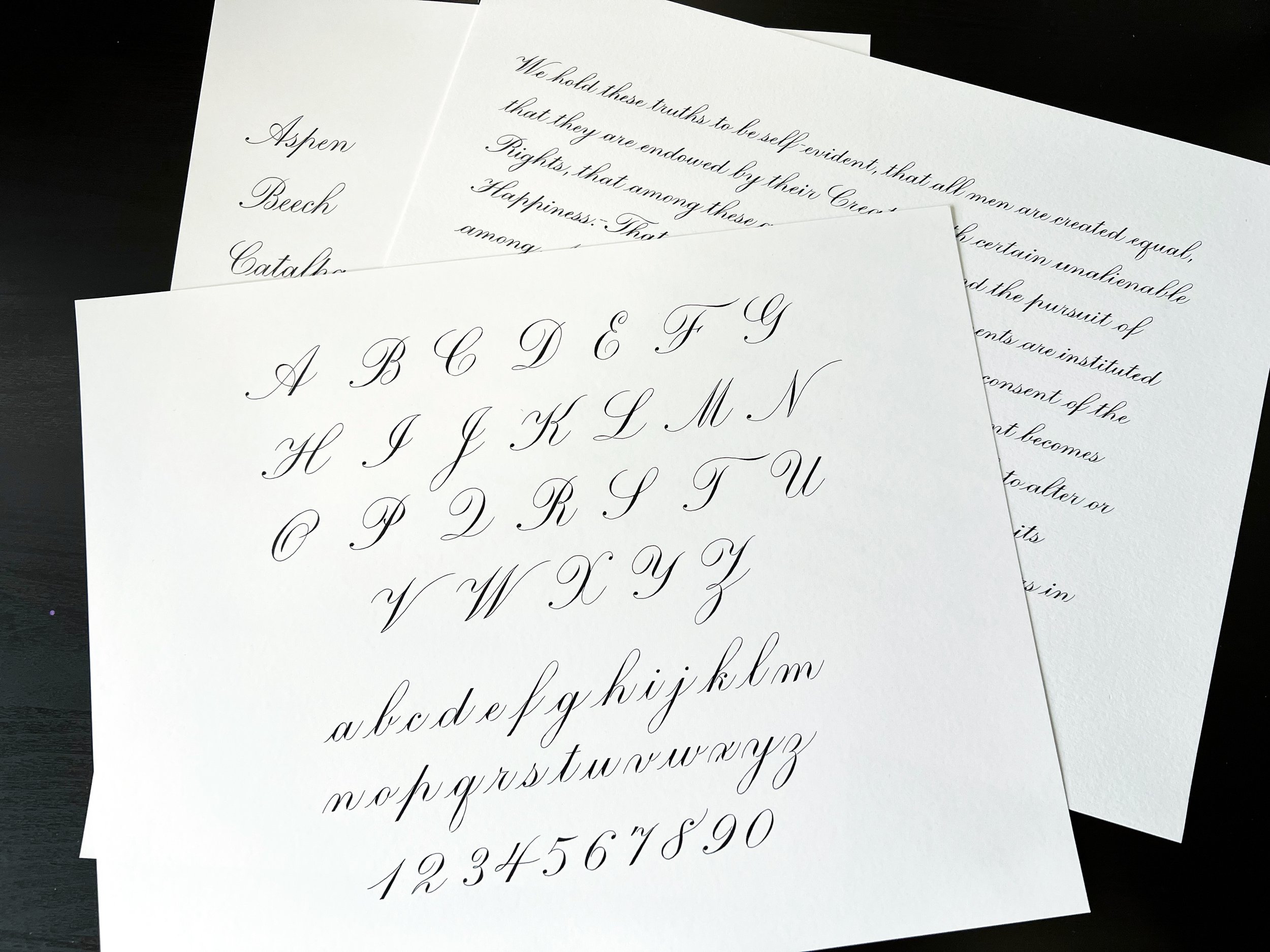

Letter Groups - Lowercase

I group the lowercase letters by the basic calligraphy strokes that they have in common.

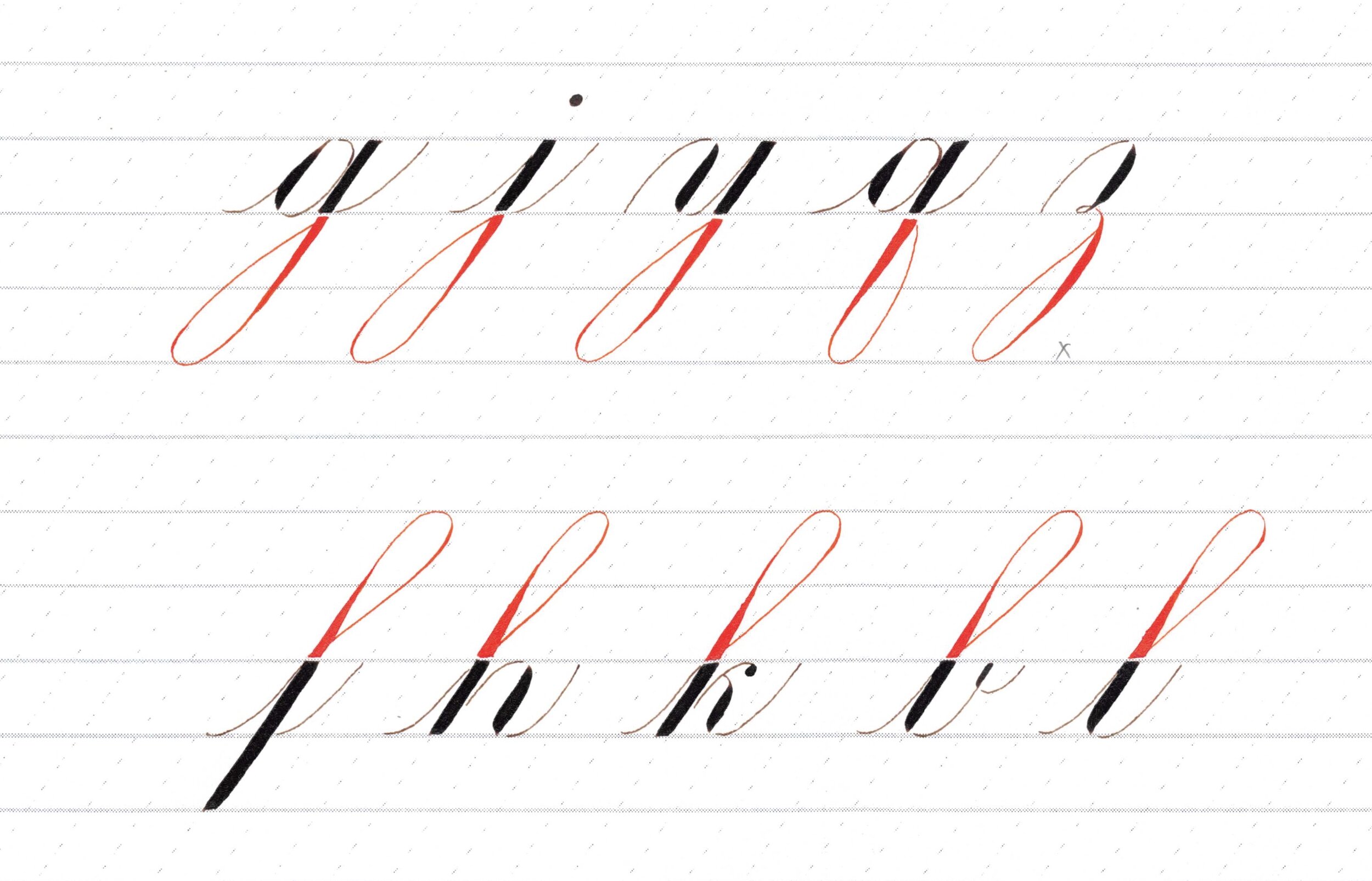

Basic Strokes - Lowercase

I go through the step-by-step process of how I personally execute the basic strokes that make up the lowercase alphabet.

Getting to Know Your Nib

Knowing how your tool works is one of the most fundamental things you need to do before jumping straight to writing words and letters. Let’s talk about how a pointed nib works in creating shades and hairlines. Let’s also go over some nib exercises that will get your muscle memory used to how your nib behaves.

Cleaning Nibs and Checking for Damage

On this post, we go over how to clean a new nib, how to tell if it’s good to go, and how to tell if it’s time to replace it.

Pen Holders and Nib angle

This post takes a closer look at the important angles an oblique pen holder has upon itself and relative to the paper, plus how it usually affects your writing.

Paper Position and Nib Alignment

On this post, I talk about how to position the paper on the table before and while writing calligraphy. Key points are finding your natural finger movement, aligning your nib to the slant lines, and keeping the range of your hand right on your sweet spot on the paper.

How to Write Calligraphy on Marble

My tips on how to write pointed pen calligraphy on marble coasters. I talk about the tools I usually use, how to erase mistakes, and how to make sure the ink stays on the marble for longer.